Geosciences Beyond the Solar System

Oliver Shorttle, Natalie R. Hinkel, and Cayman T. Unterborn – Guest Editors

Table of Contents

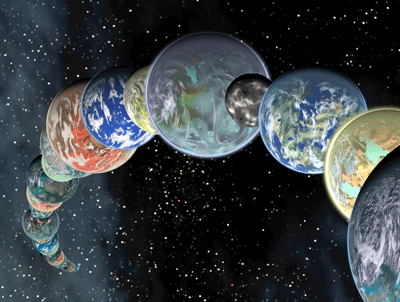

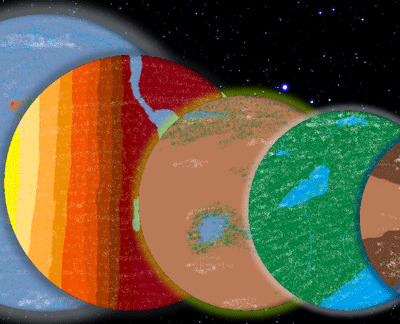

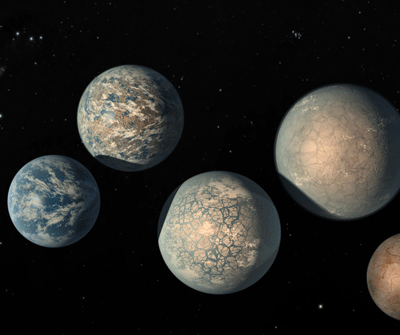

A revolution in astronomical observation has expanded the horizon of geological processes out from the handful of rocky and icy bodies in our solar system to the now thousands of planets detected around other stars (“exoplanets”). A major result from this burgeoning field is that rocky planets are the most abundant. A remarkable ∼11% of Sun-like stars host planets similar in their size and incident flux to Earth, whilst many more planets may exist in states relevant to past periods of terrestrial evolution, either trapped as perpetual magma oceans or locked into a snowball climate. This issue will highlight the myriad opportunities exoplanets represent for investigating fundamental geological processes and the opportunities for the geosciences to contribute to this exciting young field.

- Why Geosciences and Exoplanetary Sciences Need Each Other

- Compositional Diversity of Rocky Exoplanets

- Exogeology from Polluted White Dwarfs

- The Diversity of Exoplanets: From Interior Dynamics to Surface Expressions

- Constraining the Climates of Rocky Exoplanets

- The Air Over There: Exploring Exoplanet Atmospheres

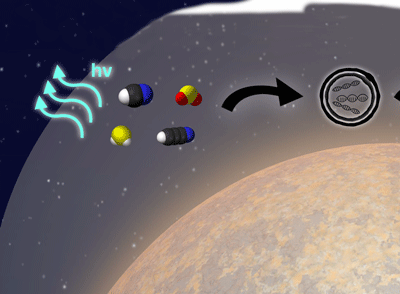

- Life’s Origins and the Search for Life on Rocky Exoplanets

CAMECA

Crystal Maker

Excalibur Mineral Corporation

The Geological Society of London

International Association of Geoanalysts

ProtoXRD

ThermoFisher Scientific

v17n5 Carbonatites

GUEST EDITORS: Gregory M. Yaxley (Australian National University), Michael Anenburg (Australian National University), and Suzette Timmerman (University of Alberta, Canada)

Carbonatites are rare, but important, igneous rocks in the Earth’s crust. They are composed dominantly of the Ca, Mg and Fe carbonates, along with many other minor and trace components. The popularity of high-tech devices—smart phones, electric motors for zero-emission vehicles, wind turbines for renewable energy—has led to a renewed focus on these enigmatic carbonatite magmas, because to make these devices requires rare earth elements and the majority of the world’s rare earth elements are associated with carbonatites. In this issue, we explore the current models for how carbonatites form and evolve in the mantle or crust, the temporal and tectonic controls on their formation, why they are so enriched in rare earth elements, and what are their economically significant minerals.

- Carbonatites: Are They the Product of Simplicity or Diversity?

Vadim S. Kamenetsky (University of Tasmania, Australia), Anatoly N. Zaitsev (St Petersberg State University, Russia), Anna G. Doroshkevich (Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy, Russia), and Holly A.L. Elliott (University of Southampton, UK) - Upper Mantle to Crustal Evolution of Carbonatite Magmas

Gregory M. Yaxley (Australian National University), A. Lynton Jacques (Australian National University), and Bruce A. Kjarsgaard (Geological Survey of Canada) - Carbonatites and their Role in Diamond Formation in the Deep Earth

Suzette Timmerman (University of Alberta, Canada), Anna V. Spivak (Russian Academy of Sciences), and Adrian P. Jones (University College London, UK) - Rare Earth Deposits in Carbonatites

Michael Anenburg (Australian National University), Sam Broom-Fendley (University of Exeter, UK), and Wei Chen (China University of Geosciences) - The Distinctive Mineralogy of Carbonatites

Andrew G. Christy (Queensland Museum, Australia), Igor V. Pekov (Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia), and Sergey V. Krivovichev (St. Petersburg State University, Russia) - Carbonatites and Global Tectonics Through Geological Time

Emma R. Humphreys-Williams (Natural History Museum, London, UK) and Sabin Zahirovic (University of Sydney, Australia)

- Shedding Light on the European Alps (February 2021)

- Speleothems (April 2021)

- Exploring Earth and Planetary Materials with Neutrons (June 2021)

- Geoscience Beyond the Solar System (August 2021)

- Carbonatites (October 2021)

- Heavy Stable Isotopes: From Crystals to Planets (December 2021)