Geomicrobiology and Microbial Geochemistry

Gregory K. Druschel and Gregory J. Dick – Guest Editors

Table of Contents

Microbes drive the interplay of Earth and life and thus control critical processes in ocean, atmosphere, and terrestrial environments. Indeed, this unseen part of our world has regulated the cycling of key ele- ments throughout geologic time. The field of microbial geochemistry is rapidly advancing our understanding of the chemical, biological, and geologic processes that regulate this cycling. Moreover, with the rapid developments in “omics” techniques (genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics), a revolution is now underway. New studies are coupling these methods with our geochemical understanding of microbial popu- lations to provide unprecedented insights into how microorganisms shape their surroundings and how geochemistry shapes microbial popu- lations. The authors will show how linking geochemical and microbial information brings understanding of the role of microbes in element cycling in modern and ancient environments.

Geomicrobiology and Microbial Geochemistry

Principles of Geobiochemistry

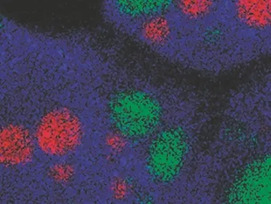

Omic Approaches to Microbial Geochemistry

Cryptic Cross-Linkages Among Biogeochemical Cycles: Novel Insights from Reactive Intermediates

Emerging Biogeochemical Views of Earth’s Ancient Microbial Worlds

Emerging Frontiers in Geomicrobiology

AHF Analysentechnik

Analytical Instrument Systems, Inc.

Australian Scientific Instruments (ASI)

Bruker Nano

Cambridge University Press

Cameca

Excalibur Mineral Corporation

Geochemist’s Workbench

JEOL

ProtoXRD

Rocks & Minerals

Savillex

Wiley

Zeiss

v12n1 Earth Sciences for Cultural Heritage

Guest editor: Gilberto Artioli and Simona Quartieri

This issue of Elements celebrates the diverse contributions that the Earth sciences have made to characterizing, interpreting, conserving, and valorizing cultural heritage. As demonstrated in these articles, Earth scientists possess a profound perception of the complexity of natural materials, they have the necessary knowledge of the ancient and recent geological and physicochemical processes acting on natural materials and on the artifacts produced by human activities, and they employ techniques essential for the investigation of our common heritage. Earth scientists greatly contribute towards a better understanding and preservation of our past. [Artioli and Quartieri (2016) Elements 12:13-18]

The Contribution of Geoscience to Cultural Heritage Studies Gilberto Artioli and Simona Quartieri

- Application of Geophysical Methods to Cultural Heritage Roger Sala, Robert Tamba and Ekhine Garcia-Garcia

- Geochronology Beyond Radiocarbon: Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dating of Palaenvironments and Archaeological Sites Constantin D. Athanassas and Günther A. Wagner

- The Earth Sciences from the Perspective of an Art Museum Federico Carò, Elena Basso and Marco Leona

- Virtual Archaeology of Altered Paintings: Multiscale Chemical Imaging Tools Koen Janssens, Stijn Legrand, Geert Van der Snickt and Frederik Vanmeert

- Advanced Synchrotron Characterization of Paleontological Specimens Pierre Gueriau, Sylvain Bernard and Loïc Bertrand

- Mineralogy of Mars (February 2015)

- Arc Magmatic Tempos (April 2015)

- Apatite (June 2015)

- Societal and Economic Impacts of Geochemistry (August 2015)

- Supergene Metal Deposits (October 2015)

- Geomicrobiology and Microbial Geochemistry (December 2015)

Download 2015 Thematic Preview

- Earth Sciences for Cultural Heritage (February 2016)

- Enigmatic Relationship Between Silicic Plutonic and Volcanic Rocks (April 2016)

- Cosmic Dust (June 2016)

- Geologic Disposal of Radioactive Waste (August 2016)

- Studying the Earth using LA-ICPMS (October 2016)

- Origins of Life: Transition from Geochemistry to Bio(geo)chemistry (December 2016)

Download 2016 Thematic Preview